I Built an Arcade Game for a Conference. Here's What Went Wrong

Amateur hour game dev, Faustian bargains with AI, and trying to do my actual job.

I work as a Developer Advocate, and despite the headaches I really enjoy it. One of my favourite things about DevRel is the diversity of work. If you get bored easily, this may be the job for you. Day to day I might find myself giving presentations, building demos, writing blogs, or attending conferences.

So I wasn't too surprised when I found myself building an arcade game to promote our new diskless Kafka product, Inkless. Inkless is an open-source Apache Kafka fork which introduces a new topic type to Kafka, allowing Kafka data to be written directly to object storage and saving users a lot of money in the process. This isn’t a story about Inkless though, so if you want to read more about it check out my other blog on the topic here.

On a call with my marketing colleagues, our ever-creative head of marketing James Bradbury pitched several ideas, including a rage room where people destroy old hard disks. Then he landed on what would become Disk Invaders: a retro arcade game where instead of shooting aliens, the player pilots a laser-firing wolf (Inkless's mascot) and fights off waves of hard drives. Additionally, instead of your score going up when you destroy aliens your cloud bill goes down as you eliminate your storage costs.

I'd made games before for game jams, so I volunteered. How hard could it be?

The rest of this blog tells that story: amateur hour game dev, Faustian bargains with AI, and the ultimate question: was the final game actually any fun to play? (And was the game actually useful for driving engagement with Inkless? You know the thing it’s my job to do).

If you’d rather play the game than read about it you can check it out here.

Building the Game

I started out simple by forking this space invaders example made by Trung Vo in Phaser3 and reskinning it with some new sprites based on some art James made.

So far so good! Then began the rapid feature creep stage of the project. In short we kept coming up with new ideas for things to add that would help make the game a hit at conferences: a leaderboard so people could compete for the highscore, music, bonus (Apache) Iceberg that could be hit for extra points, extra levels and boss levels and on and on.

I started by building out a basic home screen by adding a new scene with a “Push button to start” prompt, and threw together a rough and ready leaderboard server with FastAPI that would allow users to claim their high scores. The leaderboard server works by receiving the final score of every game via HTTP POST from the game and storing it in Postgres, then allowing users to “claim” scores by scanning a unique QR code and filling out a web form.

It was around this point that I realised that time was extremely short. All in all between conference season and other responsibilities I only had a few weeks (and a few days of uninterrupted dev time) for Current New Orleans (arguably the biggest data streaming conference in the world) where we planned to debut the game.

With no time to spare I made a Faustian bargain and started using Anthropic’s Claude to help me quickly develop and add features to get everything over the line in time for Current. This would go on to cause more problems than it solved in the short term but more on that later.

I’d been loath to use language models to generate code for personal projects because I felt like it would rob me of learning opportunities when tinkering with stuff. After some gentle encouragement from my go-to expert on all things development and AI Rachel-Lee Nabors I dabbled with using Claude and found it could be useful to help get past the initial blank slate stage of a project. So with time running out, I figured I should throw caution to the wind and see what I could get done with the time I had left.

Sidenote: I think as a result of having a gen x parent who likes to do accents I’m unable to imagine Claude as anything other than a disinterested Frenchman on the other end of the chat interface. Just me?

Quickly churning out features one after another like bonus Icebergs and a level system, I was able to throw together a v2 which included most of the features we’d chatted about and we were ready to test out the game internally.

Soft Launching the Game Internally

James shared the game at the company all-hands and we were immediately inundated with feedback. We created a separate #disk-invaders channel in Slack so people could share bugs they’d found and make suggestions for improvements.

I started working my way through the flood of Slack messages to figure out what needed fixing first. There were a few standout logical errors like unclaimed scores appearing in the leaderboard rankings. I fixed this by updating the SQL query in the highscores GET endpoint in the leaderboard API to filter out unclaimed scores.

Other issues came from my blind spots during development, like regexes I’d written that didn’t allow characters with accents and other diacritics. Additionally, there were some common threads in feedback that were more qualitative around hitboxes being unforgiving and in general the difficulty being too high.Fixing the regex was simple: changing [a-zA-Z] to [a-zA-Z\u00C0-\u017F] to include Latin extended characters solved the issue.

One thing that really caught my attention was that the game was very much not developer-proof as some of my clever colleagues pretty quickly figured out how to cheat the leaderboard and gave themselves arbitrary scores.

Whilst the regex issue was easily fixed, the issue with cheating on the leaderboard was trickier, partly because the high score was calculated client-side, making it trivial to manipulate. Cracks were beginning to show in my Claude-generated code. I'd skimmed this code and thought it looked fine, but when it came to testing it with other people issues became painfully obvious. This wouldn't be the last time I'd catch issues in AI-generated code or my approach to reviewing it.

There wasn’t much I could do to stop people submitting fake scores when playing the game on their own machines. As a temporary fix I implemented a CORS (Cross-Origin Resource Sharing) policy that meant that only machines specifically allowlisted (my laptop and the arcade cabinet) could submit scores to the leaderboard. This unfortunately put an end to the heated competition within Aiven for the top leaderboard spot. Taking my ball and going home was the best I could do to prevent cheating, that is without rewriting the whole game to be executed on the server side (although this is still something I’m considering doing for future versions).

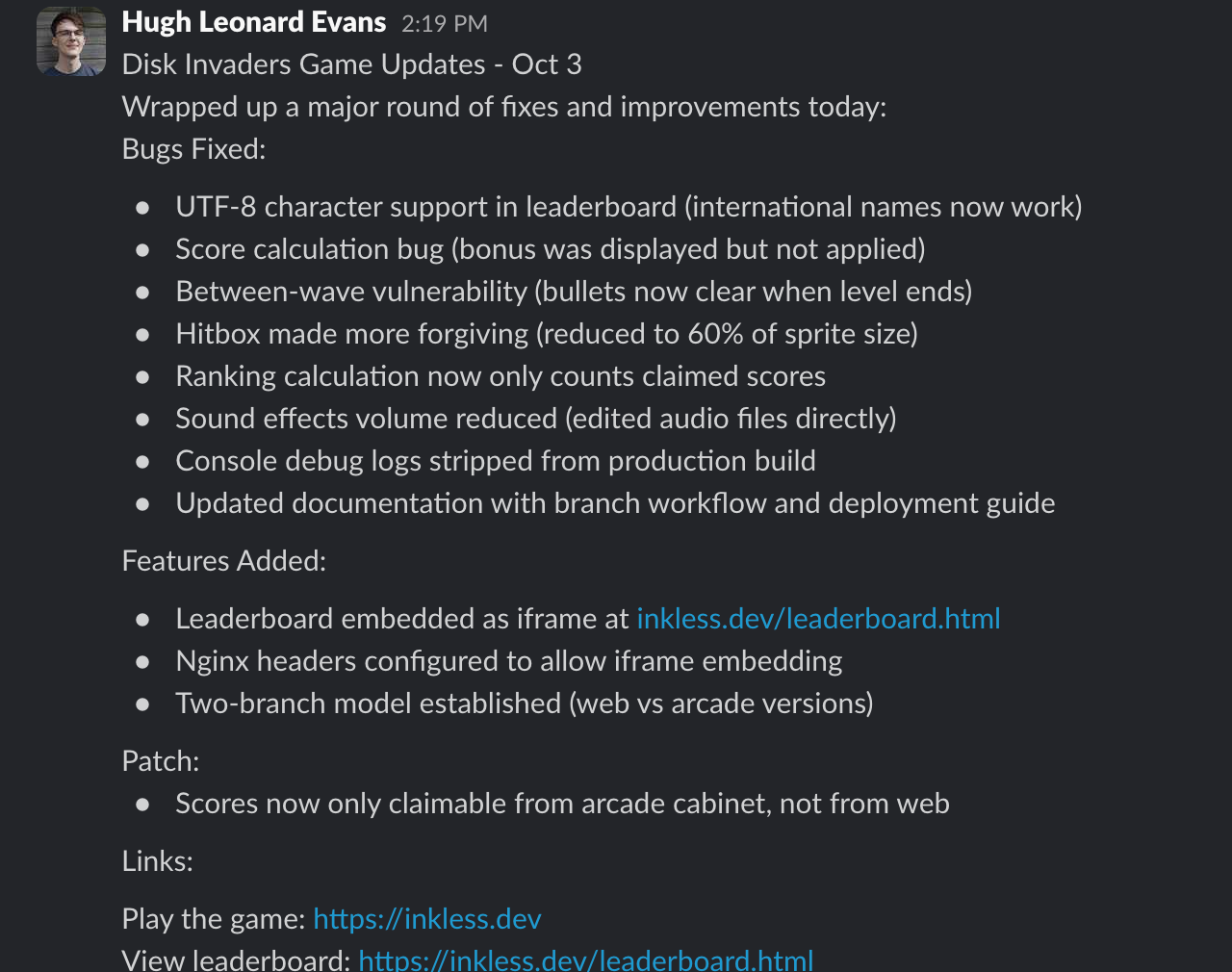

After a busy couple of days fixing everything I could and responding to the helpful feedback from my colleagues I shipped v3. I shared an update in the #disk-invaders channel to share my progress with everyone who gave feedback and tested the game.

I went back and forth with the small but dedicated group of players at Aiven like this, making small improvements until it was finally time for me to make the journey across the Atlantic to debut the game for real.

Launching the game at Current

After weeks of game development and 10 hours of flights I arrived in New Orleans ready for the game to debut on the Aiven booth. It was super exciting to see the custom arcade cabinet my colleague Jeff Meisel had built for the game and following his carefully written instructions James and I were able to assemble the cabinet and get the game running.

Immediately looking at the game on the cabinet we could see some things that needed to change. I quickly made minor tweaks changing the text on screen to describe the buttons on the arcade cabinet instead of “space” and “click” and adjusting the volume of the firing sound to make it less piercing.

As the expo hall filled up I nervously watched the first few attendees of the day trying out the game before I headed off to film some interviews with some Kafka community folks for Get Kafka-Nated (which you can check out here!)

Throughout the day I checked in on the game analytics and was encouraged to see there were already nearly a hundred games played and some high scores stacking up on the leaderboard.

Heading back to the booth for my shift later that day though my stomach sank when I saw that once again someone had encountered a huge issue I had missed in testing.

All the aliens were hitting the right hand of the screen and stacking up in a column from level nine onwards. How did this happen? How had I missed this? Once again I was guilty of not properly checking generated code. I’d used Claude to produce both the code for handling the movement of the swarms of aliens, and also to generate objects to store the starting position of the alien formation for each of the first ten levels (before randomising the formation for higher difficulties). I’d read through this code and thought it looked fine and tested it myself, but had crucially failed to account for how it would be impacted by changes I’d make later on to the alien movement speed.In response to feedback around the difficulty of the game I’d decreased the fire rate of the aliens and updated their speed to increase with every new level. When I’d made these changes I found that whilst the lower levels were easier the higher levels were much harder, which was a result I was happy with but crucially meant I couldn’t get up to level nine on my own play throughs and so missed the huge bug I’d introduced.

Embarrassed, I buried myself in my laptop and tried to figure out a fix. I did what I should have done right from the start and added some developer tools to make testing easier including a workaround to skip to specific levels for testing. I implemented a “clamp” to limit the horizontal travel of aliens to the width of the screen but this caused the performance of the game to plummet. I didn’t understand why that would be the case and with dawning horror I realised I had no idea how the alien formation logic worked. It was all Claude.

Later, with a clearer head I would be able to figure out that the performance issues were because the game was checking the position of every alien every frame, but in the heat of the moment I was unable to parse Claude’s spaghetti code I’d been throwing at the wall the past few weeks.

Defeated and without the time to rework the formation system I gave up and accepted that the best players at the conference would see my shoddy work. For better or for worse though this actually turned out to be quite a few people.

The high score from the beginning of the day had been more than doubled and players were starting to get seriously competitive. In between shifts on the booth several of my colleagues from Aiven were duking it out for first place in the Aiven team and a group from Uber put in some serious time securing an early lead. Blowing everyone out of the water though was Andy Lee who came back no fewer than six times and would go on to win with an eye watering score of $64,825.

As we packed up the arcade cabinet on the end of the second and final day of Current it felt like all in all Disk invaders had been a moderate success. The game generated a bit of a buzz around the booth and had a generally positive response. It was a lot of fun watching people battling for top spot on the leaderboard as well. In my heart though I knew the game could have been much better and I had already moved onto thinking about everything I wanted to fix in v4.

Breaking down the results

Safely back in the UK I started to unpack the data from debuting the game at Current:

- 306 games of disk invaders played

- 47 scores claimed

- 17 referrals to the Inkless product page

Current was open 8am to 4pm over both days so this works out to ~19 plays per hour which as far as I can tell is pretty good for a free arcade game! This is despite the fact that the game arguably wasn’t an amazing fit for the conference, this year attendees were mostly technical leaders looking to have serious conversations about the technology and other vendors who didn’t have a lot of time for arcade games. I think it’s quite likely the game would do better at conferences with a high foot fall and more students or junior engineers. Whilst attending AWS Summit and All Things Open where earlier this year I’ve seen similar games have much more interest from conference goers.

It’s worth noting that we were offering prizes for the winner of the game at the end of the conference which muddies the picture somewhat but my colleagues from Aiven and people from other vendors were coming back again and again to play and they weren’t eligible for the prize as it was only available for attendees.

Scores claimed isn’t a particularly meaningful metric as with hindsight the game tells you if your score is the high score or not before you claimed it, and there’s no reason to claim it unless you have the high score. This does however impact the third metric of referrals as the only time a player is prompted to read more about Inkless on the product page is on the confirmation screen after they have claimed their score. This wasn’t much of an issue though as the referral to the Inkless page was tacked on towards the end of the development process and not an issue given that we were having conversations in person about Inkless with everyone who came to the booth.

I wish I’d set up better tooling to track the performance of the game. Whilst I was able to measure the number of games played I didn’t have any data on game length or level reached which would have helped me check my tweaks to the game balance.

Based on what I was able to measure though I was pretty happy with the game and how it performed. It succeeded as an activation. I think of the contribution it made to the overall feel of our booth: drawing a lively crowd and helping bring a fun energy to our Inkless campaign.

One of my big takeaways from this project was that I really don’t want to do “vibe game development” for projects like this because it makes messy code bases that are hard to secure and maintain, particularly one with a competitive leaderboard like this. For prototyping things and quickly testing out features Claude was pretty handy.

Ultimately I blame myself for gradually replacing more and more of my own code with AI slop. More than that, I really came to hate using Claude at Current when I was trying to fix bugs in code I didn't understand: the loop of throwing an error into Claude, trying the suggestion it made and throwing any errors I got back to Claude was totally soul destroying. It made me realise that I’d cheated my brain of lots of chances to learn throughout the same project and I’m determined to not make the same mistake again.

The best part about this project was collaborating with other creative colleagues. It was really fun and some of my favourite parts of the finished project were contributions from others like the cabinet Jeff built and James’ sprites which look awesome and were hugely popular in sticker form at Current.

So was it fun? Yes. Was it useful for Inkless? Moderately. Would I do it again? Absolutely, but I’d do it very differently to the way I did it this time.

Next Steps

I’d like to take another go at building this game sensibly, from first principles, and without the over reliance on AI that soured my feelings about this project. I think this way it would be easier to build something more performant, easier to maintain, and properly secured with server side code execution so I could reinstate the leaderboard for the web version.

I’d also like to build the game on Aiven (after all it uses Postgres and we have a very good free Postgres service) to show off what we do and use it in some other content I’m working on.

Perhaps someday soon I could make another game entirely, something Apache Iceberg themed perhaps?